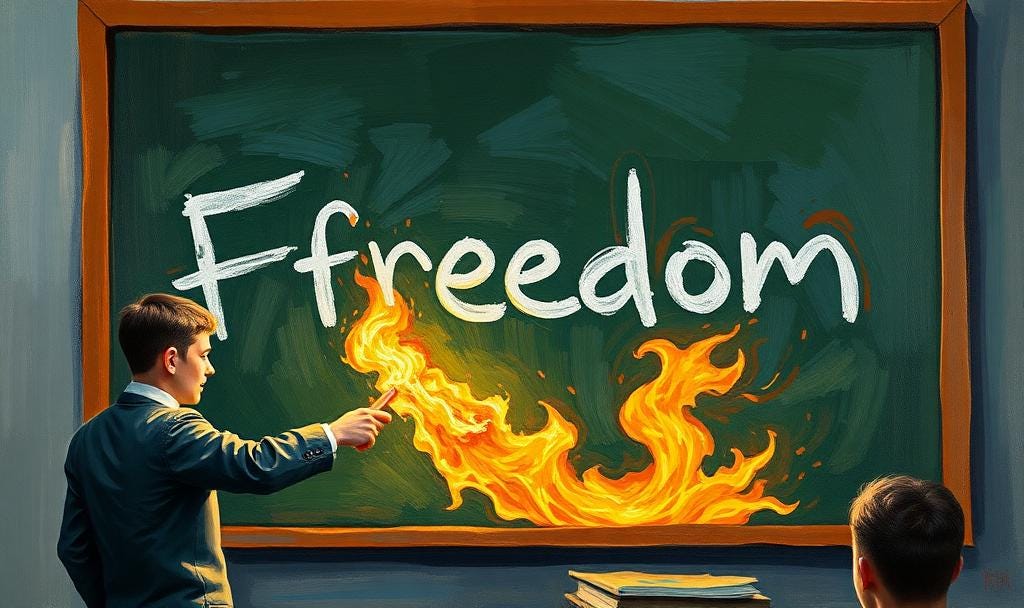

In the world of warring ideologies the idea of public education and the beliefs of libertarians seem like they would be diametric opposites. It’s hard to imagine that if you somehow tricked David Seymour and the PPTA into the same room they would have a lot in common in a debate on education. The strange thing is that public education in New Zealand has a lot in common with some basic ideas in libertarianism (if you allow a sleight of hand). Libertarians talk a lot about individuals. Individuals are the lens through which society can be viewed (which explains their hostility to the collective lens shared by indigenous cultures, and socialism). If you allow a little bit of slippage in terms, then I think you can say that the New Zealand public education system has sort of set up schools as if they are individuals in a libertarian society.

I hope that it’s obvious to you that I am not going to do a deep dive into a close analysis of this simile. Do allow me to skate out across the surface a little bit further however (out towards the thin ice). Schools have very little control from central government, they are free to do more or less what they want with their core business, and they are incredibly hostile to being told what to do because “they know best.” Obviously there are some critical differences too (zoning and unions are anti free market… actually, I have a whole other analogy about how some schools are closer to anarcho syndicalism but perhaps that’s pushing it a bit far, and maybe it just seemed attractive to write about because I think the phrase “anarcho syndicalism” sounds so fricken cool).

When the current government came in and banned phones in schools the exiting government said something along the lines of: “schools can do that already if they want to.” Which was true. Our school was in the process of doing it when the law changed. Odd though. That each school could independently decide if students having cellphones out in class was a good idea or not. Banning cellphones may seem peripheral to education until you understand that the first factor for any learning to take place is gaining attention. Banning something designed to suck attention is a straightforward decision that helps education. Such directives are rare though, and very rarely stray into the core of education. On the rare occasions when they do they are set upon and rejected like an Act supporter accidentally wandering into a Te Pāti Māori conference.

Having a universal test for reading, writing and maths seems quite an obvious thing for a country with a population of five million to do. Schools and teachers have opposed it for a variety of reasons to do with anxiety for students, setting up schools in competition with each other, and tests having flaws. While I accept these concerns up to a certain point I think not being literate and numerate causes a person a lot more than just anxiety across a lifetime, and not knowing if some schools are doing very badly at their core task is abnegating the government’s responsibility to the communities those schools serve. If it is compulsory to attend school, surely it should be compulsory for those schools to do their job effectively for the vast majority of students?

At my last Wellington-wide teacher professional development day I went to a session where two teachers talked about the literacy and numeracy programme they had developed in their school over the last few years. Everything they have done looked excellent, and has gained some promising results. My overall feeling though was: why is every school reinventing the wheel with this stuff? Literacy and numeracy is not a niche interest, and it is not a fad. Yet there is no coherent approach to it even within one city. Within one city how literacy and numeracy is tackled in each primary, intermediate and secondary school can look radically different, and have radically different outcomes. Each level in that system generally fails to talk to the next, or to use the same tests, or to even use the same techniques and vocabulary.

Now, let me climb down off my soapbox and stop throwing stones. I am in a low-ceilinged glasshouse so it would be advisable. Also, it always pays for people like me to remember to focus on the things that are within my control. Pays for mental health reasons, but also pays for my own practice and the people I impact. Anyway, complaining that everything is crap is one reason I find the internet such a triggering place inducing in me outrage, woe and feelings of futility (I generally progress in that order).

Something that really interests me is the Social Science curriculum. I spend a lot of time thinking about it (I’m a hit at parties). I also spend a lot of time listening to people on podcasts talk about Maths (again, another banger at parties). It seems as if every second person in the science of learning world is a former or current Maths teacher. This creates a problem for me because while it seems that Maths really does have a rigidly hierarchical ladder of skills and facts that need to be stipulated, this is not really the case in Social Sciences. However, I’m not quite convinced that there is no real hierarchy of facts and knowledge at all.

The Social Studies curriculum we briefly had (before it was removed) focused on a set of skills and knowledge, and tracked how those should develop from primary to secondary. The knowledge was pretty broad. For example, by the end of Year 10 students should know that “people contest ideas about identity as they challenge injustices and social norms.” Which meant that, in theory, every Year 9 or 10 Social Studies course in New Zealand should have students learn about a group challenging injustice for a chunk of time. As you can imagine this leads to quite a range of topics.

Now there’s a choice to make. Do you think that the study of specific moments of famed injustice should be mandated (everyone studies Martin Luther King for example), or do you think all schools should be free to choose? In that case I tend towards the later. How about World War Two? Should everyone who comes out of school have a basic understanding of the causes and consequences of this event, or just of the idea that events have causes and consequences attached to whatever event the school selects? In that case I would probably say the former. If you understand that social justice movements emerged across the world from the 1960s then I think selecting any example you want is fine. On the other hand, the consequences of World War Two are quite important for understanding a lot of things in the world today.

As you can see, it’s bloody complicated and very much riven by political views. What constitutes the “canon” of facts? Is teaching WWII just a western-centric world view that reinforces existing power structures? Well, yes - if it is taught that way, but no - if it isn’t.

Back to my realm of influence.

Within my realm of influence is getting together with my colleagues and creating a coherent, ambitious and wide-ranging Social Science curriculum within our school. One that not only develops in students the skills they need to leave Year 13 with, but a set of facts and knowledge that gives them a framework for understanding the world as it was, is and could be.

How hard could that be?*

___

* Super, super hard.